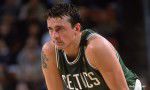

Chris Herren speaks candidly about life with addiction

October 23, 2014

On October 2, 2014 Chris Herren shared his story with the student-athlete body. Six years, three months and 28 days earlier, Chris Herren had been pronounced dead for 30 seconds.

His body was found in a car that was wrapped around a pole. He was unconscious with a needle in his arm and heroin on the front seat. Herren sees this as the best day of his life. A day more valuable than his four years imparting hope on Fall River, Mass., more valuable than his time playing for Boston College and Fresno State, more valuable than the fulfillment of his childhood dream—playing for the Boston Celtics. On this day Chris Herren started his journey back to sobriety and to the person he is today.

While he was growing up in Fall River as a basketball prodigy, drugs entered his life at a young age. Starting freshmen year of high school, Herren carried the hopes of basketball-crazed Fall River on his shoulders. As a star of his town, not only was his frequent partying over-looked, but the pressure of his legacy from such a young age took its toll. His drug use began during high school with alcohol and marijuana. Yet, in the town littered with textile mills and crumbling facades left behind by the Industrial Revolution, he didn’t stand out for excess drug consumption. Rather, he never thought that he would become entangled in drugs far beyond red Solo cups and blunts.

His drug use began to escalate when he decided to commit to Boston College. Even though scouts from all over the country had been following his every step since his freshman year of high school, Herren decided that he wanted to stay local and play close to home. At Boston College, Herren did his first line of cocaine. At 18 years old he had no idea that this one line of cocaine would take 10 years to walk away from.

Even though the use of cocaine ended Herren’s career at Boston College, he was given a second chance at Fresno State. Still Herren was unable to untangle himself from his drug addiction. Things only got worse while his dreams were unfolding right before his numb, blinded eyes. Not only did he marry his high school sweetheart and become a father, but he was selected by the Denver Nuggets in 1999 with the 33rd overall pick, then traded to the Boston Celtics in 2000. While his family and friends were watching his dreams unfold, they also watched the drug addiction that had now spiraled into painkillers unfold. Unlike Herren, they were not numb. While all that Herren thought of was getting his drugs in order to be healthy enough to make it through the pre-game rituals, his wife and kids felt the effects of the drug addiction with full force.

For Herren, getting sober was mainly about his family. At the height of his struggle there was no more basketball, there was only his personal hell. By now he had shot up with his daughter in the back seat, slept behind a dumpster with his family clueless about his whereabouts, attempted suicide multiple times, and his son had asked him why he no longer wanted to be his dad after he left his family stranded at an airport for eight hours because he was too paranoid to stay on the highway after a binge. In an interview with Fox News Herren described his life:

“I’m driving around Fall River in a panic, not feeling well, trying to find my drug dealer in time to get back home by 2:30, when my kids get off the bus so I could go sit on my couch, drink vodka, let the heroin settle in and try to figure out how to get money to do the same thing the next day.”

Things started changing around the birth of his third child. Herren had checked into a rehabilitation center in New York but within a month he convinced his counselor to let him go home to witness Drew’s birth. He had missed the births of his first two children in a drug-induced haze. He had been on Oxycontin for Chris’ (1999) and heroin for Samantha’s (2001) and didn’t want to miss the third, now that he seemed to be on the road to recovery. This would be a test for him, and he failed it. He left his wife alone in the hospital with their newborn within five hours of his birth. When he came back, he was high.

Herren said, “[His wife] shook her head and said, ‘Don’t ever come back. You broke my heart a million times, and this is the last time I’ll let you break my children’s hearts’.”

With these words Herren left for his rehabilitation center in New York. When Herren showed up high, his counselor told him the one thing that gave Herren the last push he needed to realize how much he needed, how much he wanted to rid himself of his entanglement with drugs: “Do the most noble thing you are ever going to do in your life and let your wife and kids go. Call your wife and tell her to tell your children, that you are undeserving of, that you died in a car accident.

Herren has been sober since August 2008 after spending more than a decade of his life focused solely on chasing the next high. In retrospect, Herren says, the biggest challenge is to be okay with who you are. Drugs were an escape from his faults and the pressure he didn’t know how to deal with. They were an escape from himself and his identity. Even the red Solo cups and the blunts right in the beginning, which are a part of so many peoples’ lives, were a way to escape. At the University Herren ended the account of his hell with a question for us:

“If we were children, would we look up to us? It’s hard being you 24/7, it’s hard dealing with the pressures we all face from ourselves and our community, it’s hard telling yourself that you are not who you want to be and admitting that you need to grow or that you need help. So try your best to make sure that you can answer with ‘Yes, I would look up to me’, because when your dreams unfold, you want to be there to witness them.”